Do you ever get that feeling of profound sadness or earnest yearning when thinking about a particular place or a person or a time?

It’s too nuanced to be nostalgia. It’s too intangible to be regret. It’s too poignant to be loss. The Germans call it ‘sehnsucht’, the Welsh call it ‘hiraeth’, the Portuguese call it ‘saudade’.

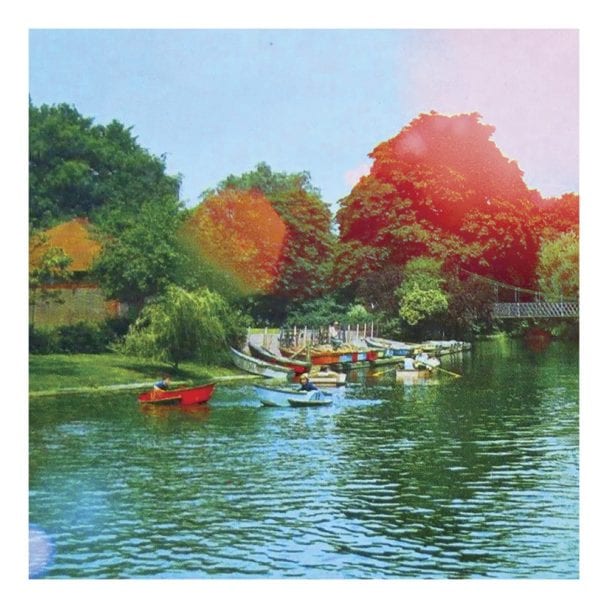

The English language doesn’t have a direct translation but Pete Rogers from Technimatic calls it Wardown. And he’s spent some time trying to capture what it is that makes him feel that way when it comes to his old stomping ground Luton. The result is an album of the same name; Wardown, a LP that exists solely to explore Pete’s relationship, thoughts and emotions about his roots.

Released this week on BMTM, Wardown is a roughly hewn weave of ambient compositions, Foley sounds, spoken word and healthy helpings of breakbeats and rave references. It’s a soulful collage that builds on the label’s spotless run of albums in the last few years – RQ, Conduct, Akuratyde, Kimyan Law – and it lands at a time of profound time for all of us. Don’t call it a lockdown album – this was written before COVID was even a thing – but we’ll be damned if it isn’t giving us those earnest yearning feels right now. We called up Pete to find out more…

Is Wardown the sound of you on lockdown?

Oh no, this just happens to be coming out during lockdown. It came out of the fact that, after Andy and I released Through The Hours in April 2019 we took an extended break. Like we always do with every album. But that album was particularly hard so we took even more of an extended break.

I remember interviewing you about it. You pushed yourselves hard on that album and rewrote major parts of it.

Yeah we did, so we took a break, and around that time I was visiting my hometown Luton a lot more than usual. My granddad, who was the last remaining family member from Luton, was ill. So I was going back there visiting him at home and then the hospital until he eventually died. He was 98, so it was no huge shock or anything like that, but when I was going back there, these ideas started circling in my mind about the idea of Luton being my home and, now the last remaining family member had left, there was nothing connecting me to the town anymore. And yet, when I went back, it had this strange power and felt a really strong connection to it.

Obviously some of that was down to nostalgia for my childhood, hearing jungle for the first time and all that kind of stuff. But there was something else tied up in it. Something a bit more complex than that. And making this album was an attempt to try and tap into the feelings that I was getting. It’s a particular feeling I’ve become fascinated with over the years; this kind of weird emotion that I can’t quite put into words. It’s like a nostalgic yearning for something just out of reach. Something you can’t quite get to. There’s a German word, which is one of the tracks on the album…

Sehnsucht?

Yes. Other languages have it, too. Welsh, Romanian, Spanish. They all try to get close to this thing which is kind of very hard to put into words and it’s where I started to come from with Wardown.

That makes it incredibly personal

Totally. The name Wardown is an area in Luton where I was brought up, and there are obviously a lot of touchstones of Luton in the album. One of the times I went back to visit my granddad I recorded him and he’s on the album. There are old tapes that I used to mix in my bedroom. I sampled a lot of those. But the album isn’t about Luton in a kind of physical sense, it’s not like ‘this is Luton’ in musical form. It’s more about me trying to tap into the emotions and feelings Luton gives me. But it’s really hard because I’m incapable of making music that makes me feel that thing. I think it’s impossible to do it yourself because you’re too inside it. But I can I hear lots of music that creates it for me. And I tried as close as I could to tap into that. Whether I did or not, it’s impossible for me to say.

What music does give you those feelings?

I’m really fascinated in ambient music and more experimental types. People like William Basinski, The Caretaker and Jefre Cantu-Ledesma. I think sonically a lot of it is to do with decay and imperfection. That was really interesting for me because whenever I’ve made drum and bass with Andy as Technimatic, or on my own as Technicolor before, there has always been a desire and a need to try and make the music sound as good and as polished and as clean and as futuristic as possible. So with this project I said ‘what if I went the other direction?’ What if you tried to degrade the music? Because this album is so much about memory, and memories are not clear or clean. They’re smudgy, they’re unreliable.

Our brains do that. Maybe to help us cope with the info we receive daily. They allow for nuance or poignancy.

Yeah. And that was the general idea and it came together quite quickly. First as ambient pieces. But the more I thought about it, and thought about my childhood and Luton, those jungle influences started coming through.

I guess The Sanctuary and illegal raves were your church growing up in Luton?

Well, I got into it in 93 and started buying records full-on in 94. But at that age I wasn’t old enough to go to any party. I didn’t have a frame of reference for it. There were free parties happening in Luton by a crew called Exodus who were very well-known free party promoters. So I would sense all of this stuff, just on the periphery. It would be just out of reach. And that idea of things just out of reach was a real important touchstone in this album. Feelings just out of reach. Memories just out of reach.

In a purely musical sense, a lot of the chords that I’ve used in it are unresolved chords that just float there and don’t resolve into what your brain expects. It was really important to have that feeling of being just out of reach, because that’s what the whole feeling I experience is like. When I try and capture it in my head, I can’t. I almost have to try and look at it out the corner of my eye. If you look straight at it, it disappears.

That must be quite liberating to approach the album with this concept having come from some very intense album processes. It’s like painting with a whole new set of brushes, isn’t it?

Yeah. And this could well be the only thing I ever do as Wardown. It’s served its purpose, I’ve explored what I need to explore.

I like that. I wanted to ask about the church bells on the album. I wondered about the significance of them. Perhaps as something that every generation in your family have heard?

That’s Luton Town Hall. And it was a sound that was everywhere when I was a kid. Interestingly, Luton Town Hall was originally burned down after the First World War… And my great grandmother was partly responsible for it.

Wow. What a woman! What was that about?

I’m unsure on details but I know she was part of a group of people who burned it down. I think they were angry at unemplyment levels after the First World War. But yeah there are lots of sounds. Things like old tapes that me and my friends recorded in my bedroom when I was a kid. There’s a little moment in the track Ferric where you can hear a conversation going on. That’s me and my mates chatting because one of my friends stormed off. I can’t remember why. I think someone had scratched his record or something. And my granddad’s on the start of Thanks For Coming. There’s also a lot of spoken word about Luton on there. Just like a collage, really.

This is effectively a love letter to Luton. I’ve only ever been to Luton Airport, and that’s my only Luton experience, so it’s never been high on my list of must-visit places. But now you’ve intrigued me.

Well this is it. Luton is famous for being shit! It’s often on the ‘shittiest places to live in the UK’ lists and has a checkered history. It’s home to the EDL. It’s been home to terror cells. But I actually had a really nice childhood there. And I really like that tension. While I haven’t lived there for 20 years, and I rarely went back after I left, and a lot of the town center is unrecognisable to me, it still has a feeling. It’s still got something about it, which is just inextricably linked to something inside me.

That’s beautiful. Have you played it to your family or maybe your friends who are on the album?

Yeah I have. One of my oldest friends from Luton. I sent it to him because he was he was a guy that I used to DJ with. We went out raving together until the late noughties. He loved it. He actually said it was the album he was waiting for me to make all along.

Nice. What do you think your granddad would have made of it? And what did he make of your music anyway?

To be honest, my granddad was very much of his time. He was a stoic man who didn’t say a lot. I think he would have been completely befuddled by what it sounded like. I don’t think he would have had any connection or touchstone to it whatsoever. Saying that, I remember him saying once ‘You’re a DJ aren’t you? I’ve got some records upstairs that you might like. Waltz records, because they’re dance records, aren’t they? When you want people dance, you put a waltz record on.’ So that’s the kind of chasm of understanding between us.

There’s still a link there. He still understood the fundamental role of the DJ. I also love the fact that this may be the only Wardown conversation we have. That this is just a moment in time and something that you needed to get out there….

Yeah. We may never have a Wardown conversation again. But we will absolutely have many more Technimatic conversations. One of the upsides of lockdown, and being unemployed, is that we’ve had a lot of spare time and have an incredible amount of music. So full steam ahead on that side.

Sick. Do you think this process will change how you go into another big Technimatic project?

I don’t think so. No. Because that is a very specific sort of creative choice to make for this album. And Technimatic is a very different thing. So I think I think that won’t be the case. But yeah, we’ve got a lot of stuff ready, and we’re really excited about it.